Tour Stop No. 8

SUGARHOUSE PRISON

“Their sickly countenances and ghastly looks were truly horrible; some swearing and blaspheming; some crying, praying and wringing their hands, stalking about like ghosts and apparitions; others delirious and void of reason, raving and storming; some groaning and dying, all panting for breath; some dead and corrupting. Their air was so foul at times, that a lamp could not be kept burning, by reason of which three boys were not missed until they had been dead three days.”

-Robert Sheffield, P.O.W.

HOME of the REVOLUTION’S DEAD

Although the British quickly captured many rebels, these prisoners of war soon raised two major questions. Where could the P.O.W.’s be safely held? And what kind of food and shelter, should they be given? The answers played out disastrously in New York, which very quickly morphed from a garrison into a city of prisons.

Majors, colonels, and lieutenants taken in the Battle of 1776 were stored in Liberty House, across from the Bridewell near the upper Barracks, and the Provost, New York’s jail, “an engine for breaking hearts” on the east side of the Common. The rest were stored nearby at the Old North Dutch Church (700-800) and the Van Cortlandt and Livingston sugar warehouses (200 or so).

Map noting the location of a few British prison ships in Wallabout Bay, and three spots where mass graves were purportedly found (Mary French, New York City Cemetery Project). Anywhere from 11,500 to 18,000 were buried along the shore. In 1808, a local Tammany official donated a piece of his estate for a tomb on what is now Hudson Avenue, between York and Front Streets (near the Wastewater Treatment Plant in today’s Brooklyn Navy Yard). In 1828, the Society built an ante-chamber. But the vault contained a tiny fraction of the bodies, later moved to a vault beneath the peak of Brooklyn’s Ft. Greene Park. There is no memorial or plaque for the rest of “America’s first P.O.W.’s.”

But while half of the soldiers captured in late 1776 died by the end of the year, the numbers only grew as the war dragged on — a total overwhelming the military, reaching perhaps 30,000. The military quickly filled the Bridewell, one of the largest buildings in New York (erected beside the Almshouse when the post-1763 depression caused the old debtor prison to be overrun). And they turned nearly every non-Anglican house of worship into a prison, too. But housing was already short because of the fires and the massive flood of soldiers and refugees. And the military could not defend the large coastal regions of Staten or Long Island. So, they decided to store most P.O.W.’s on ships anchored in Wallabout, Brooklyn’s swampy bay. Between supply-chain problems, budgeting constraints, and the general view that rebels were traitorous insurrectionists, P.O.W. welfare ranked very low on the hierarchy of concern. As many as 18,000 died from malnutrition and disease, bones washing up on New York’s beaches for many years later, the skulls on Wallabout like “pumpkins in [] autumn.” For every Continental soldier who died on the battlefield, three to four died in British captivity, mostly in New York — a higher proportion of P.O.W.’s killed than in any other US war. But as printers spread news of their mistreatment, British authority declined throughout the colonies.

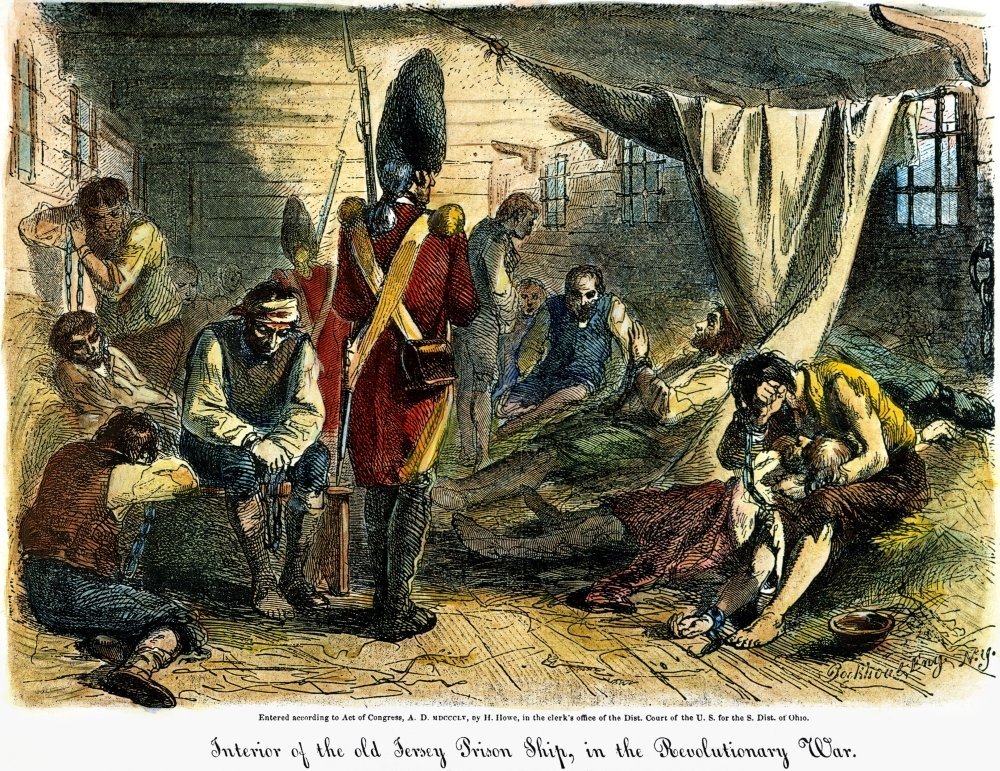

Illustration of the HMS Jersey, most notorious of the prison ships anchored off today’s Brooklyn Navy Yard.

POLITICS and P.O.W.’s

The names of the prison ships became infamous — especially the HMS Jersey, designed for 400 men, now holding 1,100, and eventually claiming the lives of perhaps 11,000 alone. The hulks were so overcrowded that prisoners had to take turns lying down to sleep in their own excrement, as vermin passed by. Disease spread easily. Rebels got just a pint of watery stew each morning, and one “kennel biscuit” at night, contributing to infection, open sores, rotting teeth, dysentery, typhus, and scurvy. Starvation was common. Some of the bodies ended up in the various graveyards outside the city. Most were cast into the harbor, or buried hastily along the shore. James Little, held on the Grosvenor, claimed that every morning “dead bodies were hoisted on deck, a cannonball fastened to them” before they were “thrown overboard with the shout of ‘there goes another damned Yankee rebel.’”

The death rate was only slightly higher than prisons at the time — for example, London’s infamous Bridewell, the model for New York’s debtor prison. But rebels used the P.O.W. experience to condemn the British, winning over many neutral and even loyal colonists. Just 8,000 of the names are known. But the victims were a diverse corps, representing at least thirteen different ethnicities, likely from all three races.

But the sugarhouse prison window near City Hall Park should remind us that British occupation meant a harsher police state for civilians, too. Many of those who died at the Provost and other jails were “state prisoners,” or rebel collaborators. And under martial law, offenses that would have been punished with a fine or a day in the stocks now carried the penalty of imprisonment, whippings, and even death. Reports of crime became depressingly commonplace. Soldiers robbed citizens in broad daylight, stealing horses and wagons, raiding gardens and homes. As Loyalists and others found themselves drawn into law-breaking to meet everyday needs, punishment and resentment grew. The suffering of P.O.W.’s also politicized many, none more famous than Elizabeth Burgin, who allegedly helped upwards of 200 escape.

Image of the Rhineholder sugarhouse near the Common (William & Rose Sts.), similar to a five-story warehouse owned by Henry Cuyler, now mispresented in the Manhattan and Bronx memorials as having been a prison. The Van Cortlandt sugarhouse next to Trinity (Stone St.) was a prison until 1777. Thereafter, Livingston’s warehouse near Golden Hill (Liberty St.) became known as “the” sugar house prison.

More than 17,000 British / allied soldiers fell into rebel hands, too. And the Patriots faced similar challenges. At first, they attempted to follow European customs of war. But very quickly they allowed P.O.W.’s to be held in a like state of torture, or just killed. “Loyalism became treason” in the war, and the “identification, demonization, and persecution of internal enemies” was central to building support for the rebellion, as historian T. Cole Jones writes. “Fear of a phantom ‘fifth column’ drove revolutionaries, elite and nonelite alike, to shocking acts of cruelty.” While there are no overall estimates yet, one British corporal noted that his men “died like rotten Sheep.” Patriots marched them across the new states, housing them in ramshackle shelters with little food, and thousands of Loyalists were simply executed under “Lynch’s Law.” More than a third of the Yorktown captives died in the last months of war.

While many Americans still regard the Revolution as bloodless, with many generations having sanitized these normal patterns of war, it was incredibly bloody. Perhaps 36,000 died, the per capita equivalent of 3.3 million today. The lust for vengeance was thus often the result of popular demand — particularly as news spread of P.O.W. treatment in New York. The number of dead was unprecedented for the century and shocking to many, especially after so many decades of regarding the British as fellow Englishmen.

-

On the P.O.W.’s, see Edwin G. Burrows, Forgotten Patriots: The Untold Story of American Prisoners during the Revolutionary War (Basic Books, 2008); Holger Hoock, Scars of Independence : America’s Violent Birth (Crown, 2017); Robert E. Cray, “Commemorating the Prison Ship Dead: Revolutionary Memory and the Politics of Sepulture in the Early Republic, 1776-1808,” William and Mary Quarterly 56, no. 3 (n.d.): 565–90; T. Cole Jones, Captives of Liberty: Prisoners of War and the Politics of Vengeance in the American Revolution (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2020); Robert P. Watson, The Ghost Ship of Brooklyn: An Untold Story of the American Revolution (Da Capo, 2017); and Kenneth T. Jackson, Empire City: New York Through the Centuries (Columbia University Press, 2002), 92-98.

On the impact occupation of New York, and the presence of British prisons, had on a nearby rural population, see Adrian C. Leiby, The Revolutionary War in the Hackensack Valley: the Jersey Dutch and the Neutral Ground, 1775-1783 (Rutgers University Press, 1962).

On Bergin, see Don Hagist, “Elizabeth Burgin Helps the Prisoners… Somehow,” Journal of the American Revolution, September 11, 2014.