Why NEW YORK CITY?

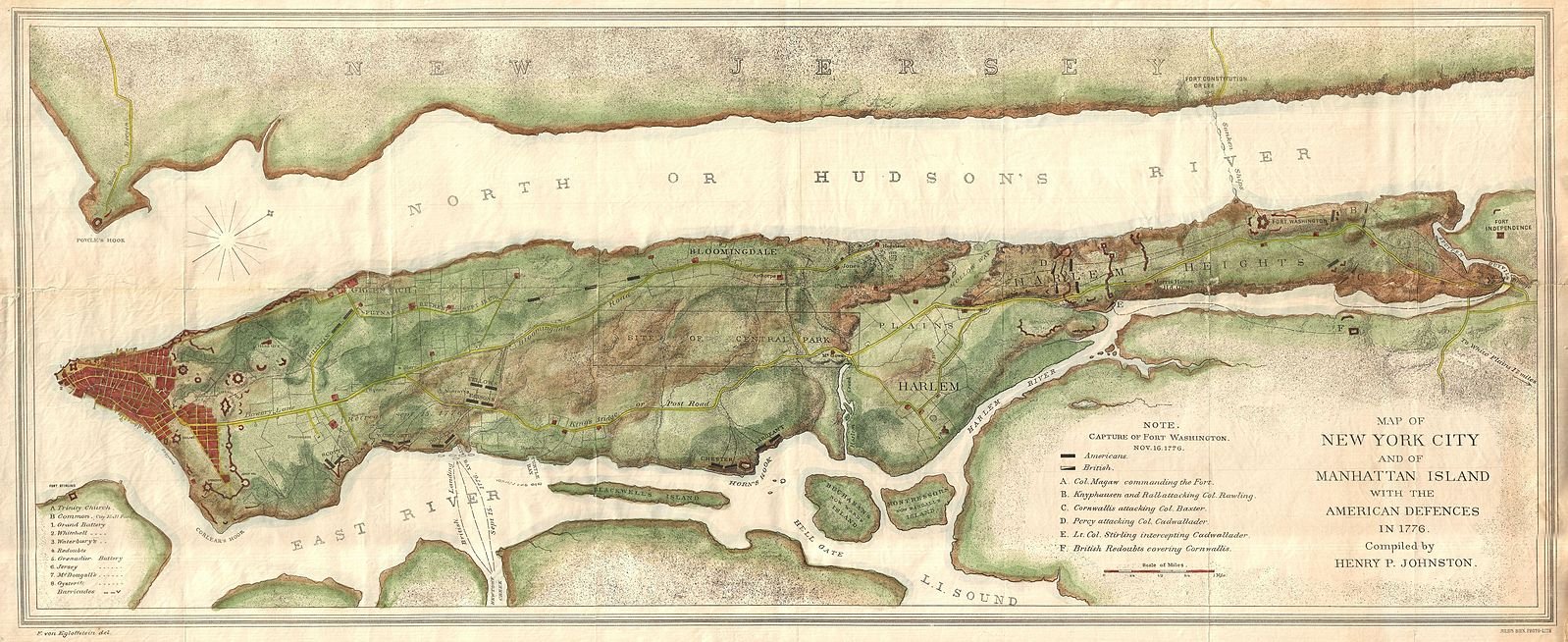

While Boston and Philadelphia dominate the imagination when it comes to America’s Revolution, New York was at the center of events surrounding Independence. By the mid-1700s, it was the military headquarters of British North America, and in many ways a kind of unofficial capital of the thirteen colonies, rumored to be the King’s favorite. Yet it had probably the fiercest reaction to Parliament’s first wave of taxes and regulation. And it faced the most draconian crackdown until the end of the Imperial Crisis, which also produced the “first blood shed in the Revolution.” The war itself literally began and ended in the city, from the earliest major battle — the largest and most important of the war — to British evacuation. And New York was the final resting place for most rebel soldiers, upwards of 18,000 dying here as P.O.W.’s. During the Critical Period or Founding, it served as the first US capital.

Yet most of that history is unknown. This project aims to correct that misunderstanding, framing New York as the city at the heart of the American Revolution.

The FIRST CIVIL WAR

Shifting the geography has powerful consequences.

Perhaps most importantly, New York offers a superior lens for viewing the Revolution as “America’s first civil war,” the framework so many historians use now. The move from rebellion to independence divided families and neighbors across the region, making bitter enemies of what had often been loose comrades. Yet that reflected opinion across the colonies — neutral and loyal subjects now estimated to have been the majority, at first. The violence and intimidation continued into the occupation, today’s outer boroughs and suburbs the victims of constant raiding by each side and the usual wartime vigilantism. Because most of the Revolution occurred nearby, the city also became a sanctuary for 40,000 refugees. And because it was the only stronghold the British managed to keep, it remained perhaps the chief symbol in the ongoing battle for hearts and minds.

New York provides a more inclusive story, too, befitting the actual history. The city was unrivaled for its diversity, home to scores of European immigrants, most of the nation’s few Jews and Catholics, and great numbers of Blacks and Natives. Each group split, to varying degrees, and had enormous roles that have often been slighted. Among other things, the war brought about the downfall the oldest and most powerful Indigenous military alliance in North America, the “Iroquois” Confederation. And it caused massive upheaval for the institution of slavery.

Although the Critical Period was less violent, it was often no less divisive, and New York remained at the center of national debate, over such things as reintegration of the enormous Loyalist population and the close struggle over ratification of the Constitution.

A More DIVERSE, COMPLEX HISTORY

New York thus offers a more diverse, complex Revolution.

It forces us to remember the divisiveness of Independence and the ideological contest that lasted until diplomacy began. It shifts our gaze from the battlefield to a seldom-considered home front, revealing the war’s intense violence and suffering — the occupation, easily the darkest and least known years in the city’s history. As British headquarters, New York demands we look at the conflict from the view of the “enemy,” too, foreign and domestic.

New York also broadens the narrative and complicates it further by spotlighting groups who became key players in this critical theater of war, erased from popular memory. The Oneida, Tuscarora, Wappinger, Mohican, Munsee, and others who fought in or around the city were among the few Natives to support the rebellion, while the Onondaga, Cayuga, Seneca, and Mohawk crippled it for a time upstate, producing one of the largest and most horrific campaigns of the Revolution, almost unknown. Likewise, the metropolitan area became “an island of freedom” for half the 20,000 individuals and families who escaped slavery during this “first Emancipation.” They became powerful allies of the British, literally guarding the entrance to their stronghold, at Kingsbridge in the Bronx. Yet just as many were eventually conscripted by the rebels — if not far more, on both sides. Indeed, it was a group of White, Black, and Indigenous mariners who enabled the rebellion to survive at the very beginning — ferrying the remnants of Gen. Washington’s army over treacherous waters from Brooklyn to Manhattan, through random heavy fog at night, while British’s entire invasion lay around Staten Island.

In New York, the otherwise familiar story of America’s founding often becomes surprising and new because of such forgotten “ordinary” men and women.

Credits

This website made possible by generous support of the Achelis & Bodman Foundation

NYC Revolutionary Trail is a project of

The Gotham Center for New York City History

at The Graduate Center, City University of New York (CUNY)

Project Director and Lead Researcher / Writer / Curator: Peter-Christian Aigner

Co-Founder: Ted Knudsen

Web Design: J. Katie Mann

Brand Direction: Brynn Heminway

Illustrations: Anita Rundles

Audio Production, Editing & Narration: Lisa Gosselin (CUNY TV), Michelle Figueroa, Chris Howerton, Peter-Christian Aigner

Video Production, Editing & Curation: Shawn Punch, Katrina Kozarek, Ted Knudsen

Educational Curricula: Anne Ballman (Hoboken Charter School) & Andrew Meyers and Tanya Gallo (Living City Project)

Advisory Board

CUNY: Carol Berkin (emerita), John Blanton, Benjamin L. Carp, John Dixon, Prithi Kanakamedala, Andrew Robertson,

Jonathan Sassi, Gunja SenGupta, Annie Valk, David Waldstreicher, Mike Wallace (emeritus)

Jennifer Anderson (SUNY Stony Brook), Myra Armstead (Bard College), Wendy Bellion (University of Delaware), Katherine Carté (Southern Methodist University), Leslie Harris (Northwestern University), Michael Hattem (Yale-New Haven Teachers Institute), Ricardo Herrera (US Army War College),

Christopher F. Minty (University of Virginia), Brett Palfreyman (Wagner College)

***

Supplemental Research and Writing: Blake McGready & Ted Knudsen

Initial Content Review: Helena Yoo, Cody Nager, Jessica Georges, Alex Gambaccini, Miriam Liebman,

Israel Ben-Porat, Arinn Amer, John Winters, Andrew Lang, Madeline Lafuse, Alex Baltovski, Evan Turiano

Additional Support Provided by Interns of CUNY’s PublicsLab (Danielle Bennett, Lisa Hirschfield, Stephanie Barnes, Thomas Blaber),

and CUNY’s Macaulay Honors Program (Gabriella Feeney)