Tour Stop No. 14

FRAUNCES TAVERN

“In this place, and at this moment of exultation and triumph, while the ensigns of slavery still linger in our sight, we look up to you, our deliverer with unusual transports of gratitude and joy…”

-Citizens Address to Gen. Washington, 1783

WASHINGTON’S FAREWELL

Washington strove to be a national figure for thirteen rather disunited states; which, for him, meant maintaining a large degree of emotional remove. In this, he was almost unerring. Officers trembled in the rare moments when he exploded in anger; for example, when they retreated from Kips Bay in 1776. But in his farewell at New York’s Fraunces Tavern, soon after the British evacuated the city, Washington finally let his emotions show. Gathering 30-40 officers who had yet to retire their commissions, he acknowledged the toll that nearly a decade of war had taken on him personally By then, his chestnut-hair had turned fully gray. Washington’s hands shook as he offered a toast: “With a heart filled with love and gratitude, I now take leave of you. I most devoutly wish that your latter days maybe as prosperous and happy as your former ones have been glorious and honorable.” The Commander in Chief then embraced, hugged, and kissed the officers, many crying in grief and disbelief.

This farewell was a fitting end. Ever since losing New York, Washington had been committed to, at times obsessed with, recapturing the city. From 1778 onward, he staged Continentals around the occupied British headquarters, gathering intelligence and waiting for the opportunity to attack. The recapture never came. But the celebrations around New York that accompanied his triumphal return in 1783 marked the conclusion of Washington’s longest military goal. Among those present was Alexander McDougall, whose imprisonment set in motion the Battle of Golden Hill, the Boston Massacre, and events beyond.

The BIRCH TRIALS

Fraunces Tavern hosted an even larger moment in the history of freedom as the site of the Birch Trials, which determined the fate of black Loyalists and runaway slaves, before Washington’s return. These “fugitives” and soldiers constituted one of the largest black communities in the North. But with independence seeming assured in 1782-83, slaveowners had flocked to New York from around the colonies in search of their property. Boston King remembered the “inexpressible anguish and terror” the population felt at the sight and thought of masters “seizing upon slaves in the streets of New York, [and] even dragging them out of their beds.”

Aware of such threats and violence, British General Sir Guy Carleton established a commission to meet every Wednesday to evaluate owners’ claims. The commission issued documents (“Birch certificates”) granting freedom to thousands, including many soldiers like King who settled in Nova Scotia. In all, 1,336 men, 914 women, and 740 children were manumitted. While modest in number, not until the Civil War would so many again gain their freedom at once. The British decision to remove the slaves, and not compensate their owners, was also historic. Nearly everywhere, slaves (and serfs) emancipated in the 1800s would be forced to pay for their emancipation, with no political debate. Haiti expunged the last of its “debt” to France in the 1950s, after liberating itself in 1791. The Birch Trials were thus an exception that remained a sore point in US-British relations for many years.

CANADA’S NEW YORK:

LOYALISTS FOUND NEW BRUNSWICK

The Loyalists evacuation was a mass exodus; proportionally, six times as large as the number who fled France’s Revolution years later. About 8,000 went to England, where a few managed to influence British colonial policy. Around 5,500 southerners went to Jamaica and the other sugar islands, bringing 12,000 slaves, which shifted the Bahamas economy from shipbuilding to cotton plantations. But the largest single contingent went to Canada, which had fought the rebels when they attacked Quebec and occupied Montreal in 1775. At least 6,000 joined the 70,000 in Quebec. The majority, 30,000 settled in the Maritimes, particularly Novia Scotia and its dependencies. The region was thinly populated (25,000) and its capital, Halifax, was just 600 miles from New York. The city remained a Loyalist haven (detailed at the next stop), but was the largest point of disembarkment, transporting more than 10,000 New Yorkers.

In the Maritimes, they also founded a new colony, New Brunswick, with its headquarters, St. John’s, built as a mirror image of New York. It’s charter was based on the city’s own, and similarly lay in a port at the mouth of the St. John’s River. The capital of the province, Fredericton, was another new city, established 84 miles up-river to encourage a bustling riverine hinterland, on the Hudson Valley model.

A group of fifty-five distinguished Loyalists petitioned the British Government for special land grants of 5,000 acres to recreate the grand manors of the lower Hudson Valley, too — although just a few such parcels were granted, nearly always as a reward for wartime military service. After pushback from middle-class Loyalists, a more egalitarian 100 acres per family became the norm, making the new colony more similar to Long Island and the new settlements along the Mohawk River.

The first governor was Thomas Carleton, brother of the former Commander-in-Chief, New York’s Sir Guy Carleton. When an Anglican Bishop was finally dispatched to the colonies to oversee New Brunswick and Nova Scotia, it was Charles Inglis of Trinity fame that won appointment. A sometime faculty member of King’s College in New York, Inglis supported the creation of King’s College, Nova Scotia, in 1788, and the College of New Brunswick in 1800.

Benjamin West’s John Eardley Wilmot, painted amidst the War of 1812, depicts a magnanimous British Empire providing for an extraordinary number of refugees after the Revolution, an historic precedent.

And the fractious politics that had defined New York in the period followed the Loyalists into exile, divisions emerging soon over which form of government the colony would take. The first election was bitterly contested, and feature the same elements of rival partisan media and taverns, pitting two strains of Loyalism against one another: those who accepted the imperial government, and those who (like many rebels) had wanted local representation within the empire, on a commonwealth model. Hundreds protested a rigged election and signed a petition to call another election. In a further irony, they were arrested for sedition, as rebels had done with Loyalists from the mid-1770s until the late 1780s. Inglis petitioned for a seminary in 1789 to “foster loyalty and prevent a second rebellion in North America,” as one historian writes. But this time the side favoring a more imperial hierarchy won out.

While the Treaty of Paris had stunned the Loyalists — one saying tartly, it “licks the feet of Congress, and of their General, and only begs not to receive a kick” — Britain provided transportation across the empire; issued provisions, tools, medicine, clothes, and seeds; and granted free surveyed land as reward for their subjects’ losses and devotion. Many of the Loyalists were never able to recreate the lives they had, particularly in New York. Their skills were a gross mismatch for the environment, under the British mercantile system: fishing and cattle-rearing more profitable than farming, and import-dependence forcing many to wander from area to area, looking for work. Over half of the 3,225 claims filed with the government in London came from New Yorkers, 468 of them women stressing their helplessness. And yet the compensation that Britain provided was virtually unprecedented — for ex-slaves, too, although the disparities were starker.

Many arrived with little more than the clothes on their back. Carpenter, tailor, vintner, miller, baker, cooper, scrivener, and innkeeper were among the most occupations in the registry. But this miniature New York was built with astonishing speed, and became a thriving port in the British Atlantic, much like the old city, but almost overnight. Inglis gushed: “Scarcely five years have elapsed since the spot on which it stands was a forest,” and yet it now boasted “upwards of 1000 houses.”

As in New York, however, 1783 marked a deadly end-point for the local Indigenous. After holding out against the French for 150 years, and the Germans and New Englanders around the Seven Years War, the Micmac and others lost the ground previously reserved for them. As hunting and trapping became a livelihood for only the poorest individuals, they also lost the basis of their independence.

The BLACK LOYALIST COLONY

More than 8,000 Black Loyalists left the United States as freemen. But just one of the forty-seven who filed received any compensation. Most sailed to England, but 3,000 went to Nova Scotia. The British promised land and support on equal terms, but the reality was far different. In Birchtown, only 183 of 649 families were given land, and just about 34 acres each — a third of the average white plot, much of it unfit to farm. Even men like Sgt. Thomas Peters, twice wounded in the service of his King, were denied grants, along with sixty-eight other Black Pioneers. Frustrated by the recalcitrance of Nova Scotia officials, Peters and several of his comrades moved to New Brunswick to attempt to gain land again. They were offered parcels some 16-18 miles away from the nearest town, without the saws, hoes, nails, and other tools the White Loyalists got. Worse still, when it became a separate colony in 1785, Gov. Carleton instituted universal male suffrage, but only for Whites. Even Peters was excluded from the franchise.

Cemetery at Birchtown, site of the first Black heritage tourism complex in Canada, memorializing the nation’s Loyalist refugees

Granted the poorest land on the barren coast, unaccustomed to thin soils and severe winters, the pioneers fared poorly. Within a few years most became sharecroppers, working land owned by White men for half its produce. Famine struck in the late 1780s, with Boston King recalling that many of the poor had to sell “all their clothes, even their blankets,” several falling “dead in the streets.” By 1791 most Black settlements were experiencing hardship, and the poorest farmers signed indentures with local merchants or sold their land.

Many of the White Loyalists frustrated with their new lives returned to the US. But “returning to a life of re-enslavement… was not an option for black Nova Scotians,” as historian Ruma Chopra writes. So they chose “a third desperate transition.” Believing there would be no future in Canada, Peters and others championed emigration to a British abolitionist colony on Africa’s western coast. In 1791-92, there was a mass exodus to another colony, Freetown, in what became Sierra Leone

The FIRST CAPITAL

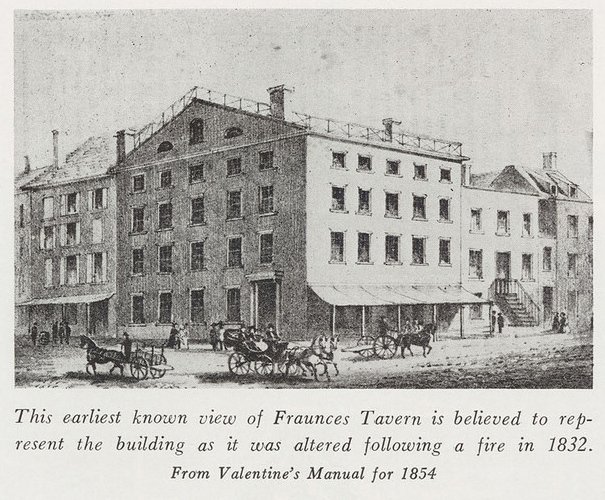

The occupation had left New York devastated. Many homes were unfit to live in. Churches and public buildings, used for hospitals and barracks and stables, were desperately in need of repair, as were the docks, barren of merchant ships and covered in barnacles, and the warehouses and streets, obstructed by numerous trenches, redoubts, and other fortifications. Rubble and garbage lay everywhere. Nonetheless, the Continental Congress decided to meet in the city until they decided on a permanent headquarters for the new republic. They moved into the legislative building on Wall St. between Trinity Church and the Merchants Coffee House, where the municipal and colonial legislature had met. Fraunces Tavern, which began its life as the home of the DeLanceys — the infamous rebels turned Loyalist (now all in exile) — served as the “first White House” and “State Department.”

It was an obvious choice, really. For all its physical devastation, the city still retained tremendous advantages. Even opponents conceded the rationale. It was larger than Philadelphia or Boston, and with the defeat of the Haudenosaunee, the state appeared primed to add new farmlands around the eastern Great Lakes basin and the Mohawk River Valley. Its geographic location and waters made it very accessible to North and South, as well as trade routes in the Atlantic economy and China. Its commercial economy, soon buoyed by Alexander Hamilton’s financial designs, also seemed to better withstand the economic depression that gripped much of the country after Independence. Plus, it was home to some of the most influential, trans-colonial figures of the era, including Hamilton, John Jay, and George Clinton. For all these reasons, New York went from headquarters of the British empire in North America and central military command during the Revolution to seat of the US Founding in the spring of 1785 and the city was radically transformed, yet again.

Until then, it was also the most intense site of anti-Loyalist reprisal in the North, as 20,000 displaced locals finally came home and voted in radical Whigs on a platform of confiscating loyalist wealth, restricting their political rights, and more. Those laws were soon overturned, however, in large part because of a young Wall Street lawyer named Alexander Hamilton. In response, thousands arrived to speculate on the war debt, and to shape the republic’s new institutions. Even as the US capital, New York remained a Loyalist headquarters. These “most forgotten” of founders grappled with the more familiar antagonists of the Critical Period. They also rubbed shoulders with nearly every major political icon of the era (Adams, Jefferson, Madison, Hancock, Randolph, Livingston), all of whom moved to New York when it became the US capital formally in 1788. Nowhere else could one find such a concentrated range of elite actors during this famous age of state- and nation-making.

-

On the Farewell, see Stanley Weintraub, General Washington’s Christmas Farewell: A Mount Vernon Homecoming, 1783 (Free Press, 2007) and Ron Chernow, Washington : A Life (Penguin, 2010).

On the Loyalist exiles, see Maya Jasanoff, Liberty’s Exiles: American Loyalists in the Revolutionary World (Vintage Books, 2012); Simon Schama, Rough Crossings: Britain, the Slaves, and the American Revolution (Ecco, 2006); Cassandra Pybus, Epic Journeys of Freedom: Runaway Slaves of the American Revolution and their Global Quest for Liberty (Boston, 2006) and "Billy Blue: An African American Journey through Empire in the Long Eighteenth Century," Early American Studies 5, no. 2 (2007): 258-87; Ellen Gibson Wilson, The Loyal Blacks (G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1976).